Dashiell Hammett and the Birth of the “Hardboiled” Crime Novel

Americans in 1930 saw a worsening of the financial crisis known as the Great Depression, the beginning of construction of the Empire State Building in New York City, and the publication of The Maltese Falcon, a novel unlike anything American literature had ever seen before. Gritty, realistic, minimalist, and unsentimental in style and tone, the novel introduced American readers to an entirely new genre of fiction: the “hardboiled” crime novel. Its protagonist, Sam Spade, a tough, cynical private investigator in San Francisco, operated in a morally ambiguous world filled with femme fatales, grifters, gangsters, and corrupt cops. Beyond its immediate impact in American literature, The Maltese Falcon has inspired generations of crime writers, including Raymond Chandler, Ross Macdonald, Mickey Spillane, Robert B. Parker, and James Ellroy, and elevated its author, Dashiell Hammett, a high school dropout, to the first rank of American crime novelists.

Americans in 1930 saw a worsening of the financial crisis known as the Great Depression, the beginning of construction of the Empire State Building in New York City, and the publication of The Maltese Falcon, a novel unlike anything American literature had ever seen before. Gritty, realistic, minimalist, and unsentimental in style and tone, the novel introduced American readers to an entirely new genre of fiction: the “hardboiled” crime novel. Its protagonist, Sam Spade, a tough, cynical private investigator in San Francisco, operated in a morally ambiguous world filled with femme fatales, grifters, gangsters, and corrupt cops. Beyond its immediate impact in American literature, The Maltese Falcon has inspired generations of crime writers, including Raymond Chandler, Ross Macdonald, Mickey Spillane, Robert B. Parker, and James Ellroy, and elevated its author, Dashiell Hammett, a high school dropout, to the first rank of American crime novelists.

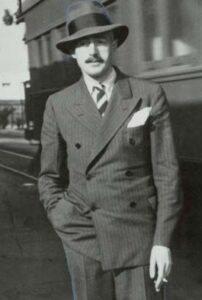

Born on a rundown farm in rural Maryland in 1894, Dashiell Hammett (image above) developed a life-long hunger for reading while attending elementary school. Forced to drop out of high school at the age of sixteen to become his family’s bread winner when his ailing father could no longer support his family, Hammett held a series of short-term menial jobs – messenger boy, freight clerk, stevedore, timekeeper, railroad yardman, nail machine operator, and day labourer. In 1915, he answered an ad in a newspaper for the Pinkerton’s National Detective Agency and remained with Pinkerton’s until 1922 (interrupted briefly in 1918 to serve in the U.S. Army during the First World War). During his time as a Pinkerton detective, Hammett acquired practical field experience and literary training in writing concise, realistic reports for his superiors. His writing skills were further developed when he briefly worked as an advertising copy writer after leaving Pinkerton’s in 1922 before turning to authoring short stories and novels on a full-time basis.

It was the pulp magazine, Black Mask, that first published Hammett’s earliest short stories. Featuring an anonymous protagonist known only as the Continental Op, the stories were based on Hammett’s experiences as a Pinkerton detective. By the end of the 1920s, Hammett had written more than two dozen short stories and two early, experimental crime novels that received passing interest: Red Harvest, a story of political corruption and gang violence in a Western mining town, and The Dain Curse, a melodrama about drugs, jewelry heists, and a secretive religious cult.

While Dashiell Hammett’s short stories and early crime novels exhibited some of his unique style of story-telling, it was the publication in 1930 of his now landmark novel, The Maltese Falcon, that solidified his “hardboiled” approach to writing crime stories. Hammett claimed that his third novel was “the best thing I’ve done so far,” and it drew widespread acclaim. The novel contained several distinctive elements that have now become common features of modern-day crime novels, and today’s crime writers may still find them helpful in writing their own crime novels:

Protagonist as anti-hero – Sam Spade is a morally complex character who operates according to his own code of ethics, a code that at times conflicts with societal norms. Neither villain nor hero, Sam Spade represents the cynical, tough-minded character who makes his own way in the world, a world that is corrupt and at times dangerous.

Femme fatale – the character of Brigid O’Shaughnessy is a complex female who is driven by her fears and events into lying and manipulating her way through the world. She is neither a pure heroine nor a dangerous villain, but a morally complicated individual who forms a psychologically challenging relationship with Sam Spade.

Minimalist writing style – Dashiell Hammett developed his lean, spare style of writing while crafting field reports as a Pinkerton detective and, later, as an advertising copy writer. His seemingly simplistic sentences hold layers of meaning, and he achieves a critical impact through precise word choices. In building scenes, Hammett includes only the essential details, allowing readers to visualize the scenes. A comparative modern-day novel, the late writer Cormac McCarthy’s No Country for Old Men, achieves a similar level of success with its minimalist style of story-telling.

Setting – the city of San Francisco becomes a character in its own right in The Maltese Falcon. Fog-shrouded streets, seedy apartment buildings, rundown hotels, and upscale homes combine to create an atmosphere that emphasizes the moral ambiguities and complexities of the characters who populate the world that Hammett creates.

Dialogue drives the story – The Maltese Falcon contains dialogue that reveals character, creates atmosphere, and advances the story line. Tension and malevolence lurk in the background of almost every scene where dialogue is present. As the late Anglo-Irish writer, Elizabeth Bowen, noted in her work, “Collected Impressions,” dialogue must be realistic, spontaneous, intentional, and express character. As she stated, “during dialogue, the characters confront one another.”

Following the critical and financial success of The Maltese Falcon, Dashiell Hammett wrote two more novels in the early 1930s – The Glass Key and The Thin Man – that also achieved publishing (and Hollywood film) success before he stopped writing entirely. He lived off the earnings from his novels and Hollywood film deals, remained politically active during the McCarthy era in the late 1940s and 1950s, was blacklisted and spent time in jail for contempt of court for refusing to name names before the U.S. House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in 1953, and then faded into obscurity before dying from ill health in 1961.